Tenzier is a Montreal-based label that releases LPs of archival recordings significant to the history of late 20th century Quebecois experimental, electronic, and improvised musics. In their own words:

Tenzier is a Montreal-based label that releases LPs of archival recordings significant to the history of late 20th century Quebecois experimental, electronic, and improvised musics. In their own words:

Tenzier is a nonprofit organization which has as its mandate to preserve, celebrate and disseminate archival recordings by Quebec avant-garde artists. Since its founding in 2010, it has coordinated the research and production of seven vinyl records (below) while also organizing events meant to bring together different generations of artists and music/film aficionados.

And the history of Quebec is indeed remarkable and worth preserving, particularly the 20th century. Most Americans likely haven’t given much thought to why a French-speaking population lives to their north, but the history of Quebec is deeply tied to the origins of the United States. Just google the French Indian War and the Quebec Act. Centuries later, during Prohibition, Montreal would become known as a sin city, the ‘Harlem of the North,’ known for its wild nightlife, drinking, jazz music, burlesque, and prostitution. This all coincided, however, with a period of time known in French as la Grande noirceur (the Great Darkness), in which the ultra-conservative Union Nationale party severely sheltered Quebecois society.

Long before Arcade Fire or Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Montreal was a important center for experimentation in music. Roger Tellier-Craig’s “Early Electronic Music in Quebec: A Brief History” aptly summarizes the changes that transformed the province into a hotbed of artistic experimentation. Like many other countries, the post-war baby boom generation refused to accept the strictures and values of their parent’s world, and the protest movements of the 1960s would set in motion unrivaled social transformations.

A 1948 manifesto “Les Refus global” published by a group calling themselves Les Automatistes is traditionally considered as the zero point for what would become the Quiet Revolution, as its calls for separation of Church and State, freedom of expression, and spontaneity would inspire a slackening of the bonds that had held the Francophone Canadians in relative stasis for centuries. Tellier-Craig writes that the manifesto influenced several key Quebecois musicians: electroacoustic composer Pierre Mercure, the (free) jazz saxophonist Jean Préfontaine, and Istvan Anhalt, a Hungarian-born composer who helped introduce electronic and tape music to Canada. As Tenzier founder Eric Fillion relates to Tellier-Craig, “With the Quiet Revolution, and the immediate post-Quiet Revolution period, you see a lot of artists working closely with the state to create an infrastructure that would provide spaces and funding for their works.”

Many of the recordings on Tenzier had never seen proper release. “Apart from Piché and Gagnon’s albums, many of the recordings from that era are from crown corporation projects,” explains Tellier-Craig. “They ended up serving as some of the earliest vinyl releases from an otherwise under-documented scene.” This is also true of the early free jazz recordings from Quebec. While Quebec’s avant-gardes were included for the sake of diversity (and “Wherever other options were available, the CBC preferred to focus more on more traditional veins of classical, jazz and folk”), without these pressings many more adventurous and innovative recordings would never have been available at all. When it comes to culture, even imperfect institutions and public funding are preferable to the whims of the commercial marketplace.

Montreal is the second largest Francophone city by native speakers after Paris, so unsurprisingly there exists a strong cultural link between the two cities. Many composers interested in electroacoustic music went to the GRM in Paris to study with Xenakis or Pierre Schaeffer. These links helped to cultivate an institutional culture in Montreal that has contributed to the direction of musical experimentation, including electronic music studios (at McGill University in Montreal and at Laval University in Québec), festivals, and a broader community of performers and listeners.

Tellier-Craig currently plays in Le Révélateur, and is fondly remembered for his contributions to Godspeed You Black Emperor!, Fly Pan Am, and Set Fire To Flames. He also played in Pas Chic Chic, with Fillion. I mention this because these inter-personal connections are precisely the kind that connects the records on Tenzier and, more generally, is indicative of the kinds of relationships that anchor the criss-crossing, hybrid musical scenes of Montreal.

When I first became a supporter of Suoni per il Popolo (another crucial part of Montreal’s vibrant and vital arts community) I picked up two of Tenzier’s early LPs Le Quatuor De Jazz Libre Du Québec’s 1973 and Bernard Gagnon’s Musique Électronique (1975-1983). In the years since I’ve reviewed three Tenzier releases, which are republished below.

Guy Thouin ~ Rien Ô Tout Ou Linéaire Un

Montreal’s Tenzier continues to unearth fascinating artifacts from across Montreal’s diverse musical heritage. Past records have ranged from visionary and singular electronic music to the distinct brand of free jazz and free improvisation that has been cultivated in Quebec. But Tenzier’s sound cannot be pinned down, just like Quebec itself. For instance, the electronic new wave duo Cham-pang’s Tant pis 81-82 sounds as unclassifiable today as it did when it was recorded 35 years ago, a fascinating and bewildering combination of electronically driven grooves and a warped pop sensibility, made truly exceptional by the power of the vocal delivery. Wonderfully bizarre, infectious, and perpetually fresh.

Rien Ô Tout Ou Linéaire Un, too, is in a category of its own, though one with none of the groove or pop. Rien Ô Tout consists solely of one composition split across both sides of the record, from artist, drummer, and improvisor Guy Thouin. Thouin was studying percussion at McGill University by this point in his career, and created this composition as an immersive sound environment to accompany “Structure immatérielle,” a laser sculpture designed by the artist Roland Poulin, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal in 1971. Poulin would become defined by his minimal, formalist sculptures and in situ works, perhaps akin to Donald Judd if he worked in wood, or Malevitch if he worked in 3D. His earlier work was confined to the flat surface, in the form of analytic drawings and collages. His first solo exhibition, inspired by countercultural Happenings, employed “laser beams and rays of light.” Regardless of medium, Poulin’s work explores the space where the fullness of form meets the emptiness of the void. While we cannot experience “Structure immatérielle” ourselves, Thouin’s sonic accompaniment seems to pursue a similar balance of the empty and the full, as implied by the nothing and all of its title.

As a vinyl recording, one side flows into the other, with no clear entrance point but rather a slowly evolving series of sonic events that continually intersect. This is not a beautiful or even inviting piece, hardly something one would typically expect to be played in an “ambient’” or “environmental” context. Instead the result is powerful and evocative, drawing attention to itself and disrupting the listener’s attempt at peaceful contemplation.

A Montreal native, Thouin’s multifaceted body of work is typical of the kind of creativity one associates with that city. Educated as an artist, having studied sculpture and contemporary art, he co-founded the Quatuor de jazz libre du Québec in 1967, one of Montreal’s innovative free jazz ensembles (whose work has previously been highlighted by the wonderful Tenzier label). Thouin also played with rock groups, and joined l’Infonie for their 1969 self-titled debut, the product of a wild rock commune which produced four albums at the intersection of rock, jazz, classical, and pop which influenced Quebecois progressive rock.

Rien Ô Tout Ou Linéaire Un nods somewhat towards the sororities one might expect of free improvisation, however the results have clearly been ordered and composed. Even when individual elements can be quite abrasive, there is an apparent order and restraint guiding its perpetual movement. The primary sound objects consist of screeching vibrato pitches and crashing percussion, ornamented with the occasional staccato notes on a dismantled piano. Not quite electroacoustic music, as most of the sounds are untreated, the use of magnetic tape is nonetheless central Rien Ô Tout‘s aesthetic. The screeching pitches originate from a modified koto, a stringed instrument that is the national instrument of Japan. The koto has moveable bridges, for tuning, and as one plucks with one hand one can modify pitch by bending the string with the other. Here, rather than plucked, the koto seems to be bowed, producing a sound more akin to a kokyū or erhu, seemingly without any attempt to produce a pleasant tone. A cloud of percussion comes and goes, generally mallets beating symbols with the occasional crash. Reverse tape noises and the general constructed quality of the piece suggests extensive tape editing and manipulation.

If Rien Ô Tout Ou Linéaire Un seems to reject pleasant sounds in favor of abrasiveness, startling the listener to attention, perhaps we would do well to consider the historical context. Poulin’s show at Montreal’s Museum of Contemporary Art, which ran from October 21 to November 7, 1971, occurred one year after the October Crisis, in which Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures act in response to the kidnapping of Quebec’s Deputy Premiere and a British diplomat by Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), effectively imposing martial law on the province. While Quebec’s Révolution tranquille was considered to be “quiet,” this was a most unquiet time, and sometimes noise is called for. Jazz Libre, of which Thouin was a founding member, certainly embraced improvisation as a means of bringing about radical change in Quebec, and in their case a radical avant-garde aesthetic reflected their politics, even establishing an artistic commune for activists and artists to live collectively and share ideas. 1970 was a defining year for Jazz Libre’s sound, as they continued to embrace avant-garde music. I can only assume that Rien Ô Tout carries with it at least some of the same political drive. While the efficacy of such activities is open to debate, 2018 feels like the right time to re-open the question. (Joseph Sannicandro)

Yves Bouliane ~ Champ (10 opérations)

Champ (10 opérations) is the solo work of a pillar of Montreal’s 1970s free improvisation scene. A skilled improviser, this piece is indeed a composition, recorded in 1977, and stands as a momentous and perplexing document of that time. This suite of compositions is a shockingly singular exploration of experimental extended technique for the cello. Despite being solo compositions, one can hear the influence of years of free improvisation, of the dialogue between artist and his instrument. A remarkable documentation of Bouliane’s creativity and endurance as a performer and improviser.

“Champ (10 opérations)” – Extrait (Excerpt)

As a young man in the early 1970s, Yves Bouliane studied double bass with Roland Desjardin at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal, though he’d already had a few years improvising on the scene with Robert M. Lapage (clarinetist/saxophonist, musique actuelle composer, as well as cartoonist). Bouliane briefly performed with the Jazz libre du Quebec ensemble (see TNZR 51), and along with some comrades founded Montreal’s Experimental Music Workshop, an important node in Montreal’s vibrant creative scene of that period. Though Bouliane switched gears to study painting (the artwork of this album is his), he never abandoned music. In 1985 Bouliane recorded a bass/drum duo Masse au 1/3 contrôle with John Heward, who is still gigging and is without a doubt one of the best improvised drummers I’ve come across.

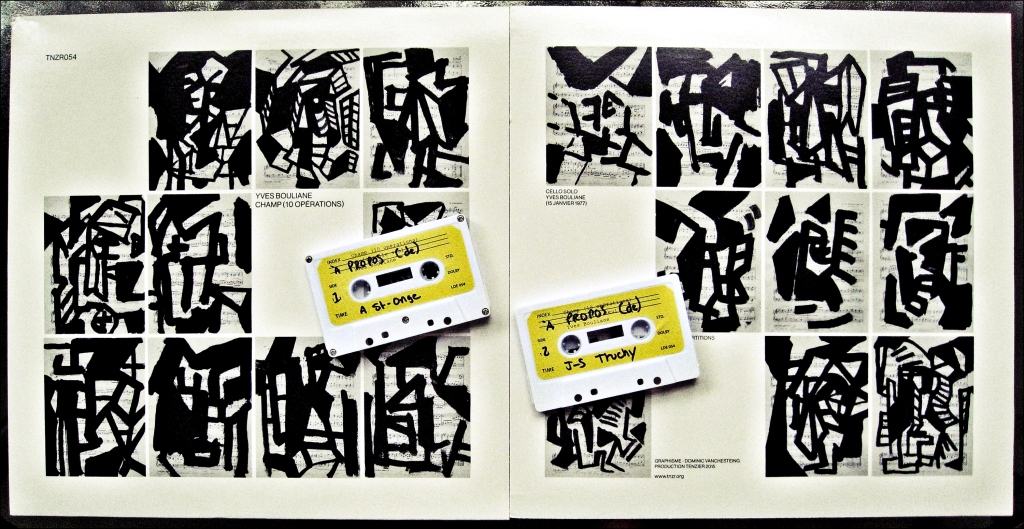

In 1977 Bouliane composed Champ (10 interventions) and Champ (10 opérations), for bass and cello, respectively. The former will see a release interpreted by Ensemble SuperMusique in the near future. The history of the latter is something a bit different. Rather than wonder how to realize such unique compositions, we have Bouliane’s original 1977 recording. At the time, it was released in an edition of only 10 handmade cassettes. Tenzier, with some help from Los Discos Enfantasmes tape label, has paid tribute to this fact with a limited tape release of their own. Tenzier invited two contemporary Montreal musicians, J-S Truchy ( Fly Pan Am, Set Fire To Flames, most recently Avec Le Soleil Sortant De Sa Bouche), and Alexandre St-Onge (Shalabi Effect, Feu Thérèse), to contribute their own reinterpretations and presented a limited edition of 54 cassette facsimiles of the original to accompany the release. Their reinterpretations capture the intensity and spirit of the original, but coaxing rather different sounds from their instruments.

Champ (10 opérations) is truly remarkable as a sustained exploration of a limited field. The term “extended techniques” associated with free improvisation conjures what by now seems a recognizable (if not codified) idiom, but the playing on display here is incredibly restrained despite the fact that Bouliane never ceases moving, and there always seems to be multiple sounds occurring at once. Rarely, however, is a string bowed or plucked. Scraping, banging, implications, constant movement are harassed and directed, spreading out into a fertile field of sound. (Joseph Sannicandro)

« À propos (de) »; a musical homage prepared by Alexandre St-Onge and Jean-Sébastien Truchy (in collaboration with the Montreal label Los Discos Enfantasmes) is now sold out, but you can listen to two excerpts at the links below.

Gisèle Ricard ~ Électroacoustique (1980-1987)

The history of experimental music in Quebec is quite interesting. In part because it is the homeland of French speakers in North America, la belle province has maintained closer aesthetic ties to the “Old World.” It’s not surprising that the GRM and Xenakis have been the major influences on electro-acoustic music in Quebec, which admittedly is a rather academic pursuit wherever it manifests. Yet in Montreal at least, artists freely traverse different scenes, with the classical avant-garde bleeding into free jazz and rock and back again. The designation of musique actuelle is vague enough to unite composers, academics, and performers who practice non-commercial disciplines, including free improv, electro-acoustic, avant rock, and experimental electro-acoustic works. Perhaps best documented by the Ambiances Magnetiques collective, the range of challenging music produced in Quebec is truly remarkable. This non-genre is not confined in any way to Montreal, but is actually most closely associated with the annual (legendary) Victo music festival. And Quebec City had its own hot bed of electronic composition, as this release documents.

The history of experimental music in Quebec is quite interesting. In part because it is the homeland of French speakers in North America, la belle province has maintained closer aesthetic ties to the “Old World.” It’s not surprising that the GRM and Xenakis have been the major influences on electro-acoustic music in Quebec, which admittedly is a rather academic pursuit wherever it manifests. Yet in Montreal at least, artists freely traverse different scenes, with the classical avant-garde bleeding into free jazz and rock and back again. The designation of musique actuelle is vague enough to unite composers, academics, and performers who practice non-commercial disciplines, including free improv, electro-acoustic, avant rock, and experimental electro-acoustic works. Perhaps best documented by the Ambiances Magnetiques collective, the range of challenging music produced in Quebec is truly remarkable. This non-genre is not confined in any way to Montreal, but is actually most closely associated with the annual (legendary) Victo music festival. And Quebec City had its own hot bed of electronic composition, as this release documents.

Tenzier is a non-profit label dedicated exclusively to releasing archival quality records from Quebec’s storied past. The work of such labels is truly invaluable, as such music is certainly of value to posterity even if it might have limited commercial appeal at present. Run by former Pas Chic Chic drummer Éric Fillion, the label is committed not only to preserving these works, but seeing that they circulate.

Earlier releases have documented Free Jazz, cut-up tape soundtracks to experimental cinema, and electronic music. Though pure electronic synthesis often takes center stage, the role of tape in these transformations shouldn’t be understated and there is a clear influence of musique concrete techniques. (I’ll leave the discussion as to whether or not there exists a “Montreal sound” to others.)

The latest from Tenzier is an LP by Gisèle Ricard, of whom I’d never heard. But this is rather the point, so don’t let the lack of familiarity put you off. Featuring three pieces realized between 1980 and 1987, each piece lives and breathes, making fascinating use of the stereo-field to create an organic sense of space and movement. Unlike Tenzier’s earlier foray documenting electronic music, which drew on the activities of McGill University’s formidable music technology program, Ricard was based at Laval University’s School of Music in Quebec City. So if there is a Montreal sound, this isn’t it.

“Je Vous Aime” (1987) is electro-acoustic bridal music, a tape collage composed out of sound fragments. The pitch-shifted vocals may have lost some of the power they had two and half decades earlier (in that the technique is almost common place even in popular music these days), yet it still suits the surreal mood of the work. It’s tender, evocative, and a bit strange. I may be misunderstanding somehow, but I think the title is suggests this as well. In French, normally you’d say ‘Je t’aime’ to say I love you. Vous can mean you-plural, as in addressing a group, or it can be a formal, polite way of addressing someone you don’t know very well. In either case, it makes for an odd wedding. I imagine she is addressing the many chanteurs and chanteauses whom she has cut up to make this composition. Through the magic of tape music we get a resounding chorus of “We do.”

“Immersion” (1980) is the earlier of the three pieces presented here, realized on an AKS synthesizer (you know, with the little pins, in the suitcase? A great little synth.) So far as I can tell the primary occupation of the piece is with manipulating the sense of spatiality while adjusting the various filters. Perhaps a bit dated in some ways, it is still an expert manifestation of what a trained mind can do with the limits of these early synths. And yes, a lot has been done with and to synthesizers since then, but don’t focus on those aspects, focus on what she’s doing within those confines (which seemed rather expansive at the time, I’m sure.)

“Immersion” (1980) is the earlier of the three pieces presented here, realized on an AKS synthesizer (you know, with the little pins, in the suitcase? A great little synth.) So far as I can tell the primary occupation of the piece is with manipulating the sense of spatiality while adjusting the various filters. Perhaps a bit dated in some ways, it is still an expert manifestation of what a trained mind can do with the limits of these early synths. And yes, a lot has been done with and to synthesizers since then, but don’t focus on those aspects, focus on what she’s doing within those confines (which seemed rather expansive at the time, I’m sure.)

The second side features just one long composition realized in 1982 with Bernard Bonnier, a piece of music theatre for electronic instruments, two comedians and a visual designer. (Most unusual instrumental list of the year?) It is from this visual performance that the album artwork draws, and is a clear highpoint of the album for me. The utilization of electro-acoustic instrumentation grants the piece a flexibility and life compared with the previous compositions, a sense of openness that augments the electronic timbres. Bonnier served as Piere Henry’s assistant in the early ‘70s, and combined with his expertise, Ricard produced a masterwork in “Une autre création du monde.”